We have previously discussed at the Nature of Peace about the usefulness of using remote sense analysis to monitor environmental change in conflict-affected areas. Following up on this, we share in this post some of the findings from our study on vegetation and environmental change in Northern Uganda, published in the The Journal of Environment and Development (open access here). For an in-depth presentation of the research (design and findings) please check our article.

In peacebuilding efforts, it is important to recognize how armed conflicts impact the environment, not only through ecosystem damage and biodiversity loss but also through opportunities for ecological recovery. Both of these outcomes can shape post-conflict paths toward peace and development. In Northern Uganda, the conflict from 1986 to 2008 had a significant effect on both the communities and their surrounding environment. While some regions experienced environmental degradation, others saw ecological recovery. Understanding these dynamics is key for managing natural resources in post-conflict areas and supporting peacebuilding efforts. We explore how vegetation in Northern Uganda changed during and after the conflict, analysing what may have driven these changes and their implications for lasting peace and sustainable development. By examining satellite imagery and existing research, we see a post-conflict ‘greening’ alongside a more balanced pattern of both vegetation loss and recovery at the regional scale. If these changes are linked to agricultural expansion, how agriculture is managed in relation to natural ecosystems will be crucial for peace and development.

Image credit: Getty Images. Mark Newman.

Introduction

There is increasing global recognition that armed conflicts have direct impact on the natural environment (ecosystems, natural resources, biodiversity), as evidenced by the growing number of research (1), policies and reports (2) as well as institutions or organisations who have incorporated peace concerns in their environmental agendas or environmental or ecological concerns in their peace agendas.

While empirical evidence from diverse regions of the world shows that armed conflicts trigger processes of environmental degradation on the ground, less is known about how armed conflicts might also contribute to processes of ecological restoration. This is the case, for instance, of areas previously dedicated to farming, abandoned due to displacement. Both processes – degradation and restoration – have profound consequences for sustainable peace and development in the aftermath of conflict.

The armed conflict between the Lord Resistance Army (LRA) and the National Resistance Movement (NRM)/Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF) between 1986 and 2008 in Northern Uganda had profound impacts on local communities and their natural environment (3). The impacts were however not geographically evenly distributed. While some geographical areas have gone through environmental deterioration – due to natural resources overexploitation or infrastructure development – other areas have experienced ecological restoration (4). This historical trend is central to understanding post-conflict natural resource exploitation and management.

In 2013, the Advisory Consortium on Conflict Sensitivity (ACCS) conducted a comprehensive study on post-conflict drivers of conflict in Northern Uganda and concluded that one of the ‘four most serious threats to long term peace’ across the region related to the natural environment (such as competition over natural resource exploitation and access to land; including oil, grazing, forests and over reserves, but also environmental deterioration and natural disasters) and such threats could ‘inevitably return to overt conflict’ (3). In 2015, the Government of Uganda (GoU) stated that tensions over resources (particularly access to land) among people could threaten any peace and development intervention set up to stabilise the region (5). Together with urban growth, high poverty and low education levels, local communities bear a high potential of relapse into violent conflict (6).

Northern Uganda currently faces numerous environmental challenges and conflicts driven by expansion of plantation agriculture, oil exploration and exploitation, and urban growth (7). Nardi (2024) understands that the expansion of the resource frontier towards the Northern region of Uganda during peacetime – lead by large-scale capital – has generated tensions with local communities whose knowledge and understanding of the natural environment are not considered in such economic projects (e.g. oil exploitation, mineral exploration, agribusiness, hydro-energy, etc.). In addition, a growing population demanding energy and food has triggered land use and land cover change which patterns and extent are of environmental concern (6). Scholars have more recently stated that land use and cover change ‘is having a wide range of impacts on the environment and the people of Uganda at different spatial and temporal scales’ (8). One of such impacts can be found in environmental or climate-induced migration (9).

We argue therefore that prospects of sustainable peace and development cannot be properly understood without considerations of the natural environment. The purpose of this article is to understand (a) how vegetation activity has changed in Northern Uganda during and after the armed conflict and (b) possible drivers of environmental change explaining such vegetation activity change. The aim is (c) to comprehend potential implications of environmental change on the sustainability of peace and development.

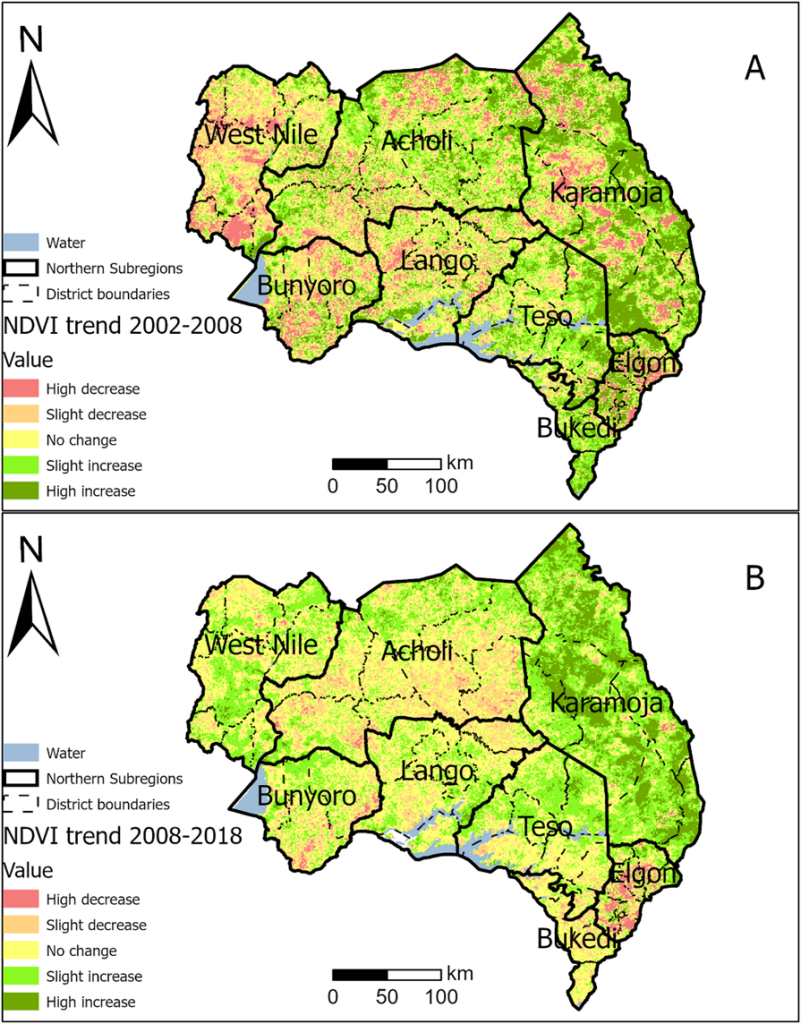

We analyse environmental changes by examining shifts in vegetation activity at the sub-regional and district levels during the conflict period (2002–2008) and the post-conflict period (2008–2018). Additionally, we observe vegetation activity on a regional scale during the post-conflict years (2008-2018). Our descriptive analysis provides insights into the spatial distribution of vegetation activity trends, using satellite imagery time series to assess the final years of armed conflict and the subsequent recovery period.

Furthermore, we seek to explore the drivers behind these changes in vegetation activity during the post-conflict period, comparing them to trends observed during the conflict in four key sub-regions: West Nile, Acholi, Lango, and Teso. For this, we draw on secondary data from land use and land cover (LULC) studies, predominantly from academic sources. Our explanatory analysis helps us explore the environmental implications of these changes, such as ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss.

By examining both trends and drivers of vegetation/environmental change, we aim to highlight the crucial role of the natural environment (e.g., as natural resources) in promoting peace and sustainable development. Our findings serve as a foundation for future fieldwork-based research aimed at understanding environmental dynamics in the region, with implications for policymaking and peacebuilding efforts.

The Natural Environment During Conflict and Post-conflict in Northern Uganda

During the second decade of the armed conflict between LRA and UPDF – around 1996 – people from Acholi sub-region were moved to internally displaced people’s camps (IDPC). The relocation of around 1.4 million people led to an uneven spatial distribution of natural resource overexploitation in camps and around them. Between 1985 and 2002 woodlands were lost around towns (Gulu, Kitgum, Lira) and IDP camps due to natural resources overexploitation as a consequence of internal migration and expanding human population which resulted in conversion of natural vegetation to farmland in the southern districts of the region (e.g. Lango).

The paradox is, nevertheless, that the armed conflict worked also as a driver for environmental protection (e.g. vegetation preservation or restoration) in other areas. Vegetation was restored in some of those territories where the LRA rebels were based, or with no easy access by most of the local population. This might explain the higher level of vegetation conservation during that period in particular woody cover west and north of Kitgum where the LRA has been most active (4).

The abandonment of some areas (both by people and livestock) and the concentration of population in others have been clear drivers of vegetation change. However, other factors might be explaining this unequal geography of environmental change, such as biodiversity loss (e.g. due to habitat destruction), population growth, expansion of urban settings and/or farmland, or temporal and spatial variations in the weather (e.g. making some areas more prone to droughts than others). This might be indicating that ecological connections of Northern Uganda with other geographical regions could explain environmental change during conflict time and not only the consequences of the armed conflict itself (e.g. destruction of wildlife habitats that work as corridors).

From 2007, once the violence against civilians deescalated and people started leaving the camps, evidence shows that the Northern region of Uganda became the scene of socio-environmental transformations: urban growth, expansion of charcoal production, logging and high-value timber extraction, oil and mineral exploration and exploitation, agribusiness, land enclosure for nature conservation and the consolidation of new camps for displaced migrants from neighbouring countries.

Various factors, ranging from local to global scales, might explain the environmental changes occurring on the ground in Northern Uganda. According to academic research and policy reports, diverse processes of environmental change – mostly connected to vegetation degradation and biodiversity erosion – are motorised by the increased local population and the insertion of the region into the global economy. We observe, for example: (a) the expansion of farmland for local food production, (b) the increasing charcoal exploitation for energy consumption mainly in Uganda but also bordering countries (8, 10), (c) the increasing oil, mineral and timber exploitation for foreign markets (7), (d) the setup of camps for hosting Sudanese refugees (11), (e) the expansion of large scale agriculture (monoculture plantation) for extra regional markets (11) and (f) the enclosure of forests and savannas for biodiversity conservation and tourism (13). Urban population growth seems relevant to understanding processes of environmental deterioration in particular. Urban population in Uganda increased from less than one million persons in 1980 to about 3 million in 2002 and 7.4 million in 2014 (14). This trend translates also into land cover and use change, usually resulting in environmental degradation and biodiversity erosion. Urban areas have increased with a growth rate of 52% at the national level between 1996 and 2013. In the context of Northern Uganda, it can be observed clear gains in urban land uses, remarkable in Acholi sub-region where there has been 327% increment of urban land area during the period of 1996–2013, but also in neighbouring Lango sub-region during the same period (15). Research has shown that ‘the war economy and the subsequent growth and development of Internally Displaced People’s camps (IDPs) which have been upgraded to urban centres explain the observed patterns of growth in Acholi region’ (15, page 262).

Most of the population of Uganda uses biomass as the main energy source (16; 17). In Northern Uganda, evidence shows that savannas and forests restored during the conflict turned into a rich source of charcoal during post-conflict, particularly to be traded outside the region (18). This particularly the case due to regions previously supplying Kampala were already totally depleted (19).

Research observed that during the post-conflict and peacebuilding period, new actors arrived in the Northern region and scaled up natural resource extraction and trade, for charcoal production and valuable timber logging (6). The fragile land tenure and unstable land access seems to be pushing people to cut down trees or overexploit soils as they are uncertain about the long-term access to natural resources from their land plots (20). This has further accelerated an environmental degradation process, according to different sources.

Unsustainable charcoal production has been reported in Acholi, West Nile, Lango and Teso to name a few of the Northern sub-regions where charcoal is produced and traded in and out of the region. The overexploitation of timber and charcoal production is recognised as one of the major environmental concerns in the North region. For some, ‘charcoal production, and its particular destructiveness, should be understood as a continuation of the violence of the 1986-2006 war between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Ugandan government’ (6, page 242).

During the period 2010-2015, an estimated number of 250,000 ha of forest per year were lost in the entire country, while between 1990 and 2015, the annual average of lost forest was 122,00 ha. (21). At the same time, forest cover outside protected areas was reduced from 3,331,090 ha in 1990 by 34% in 2005 and by 68% between 2005 and 2015 (21). This might be indicating that areas with high vegetation cover (both forests and grasslands) have been subject of exploitation during peace times (post-conflict period) in the country.

Activities around oil exploration and exploitation along the Albertine Rift have been reported to be detrimental for natural vegetation and polluting (7). Construction activities (e.g. roads, bridges, pipelines, refineries) might explain losses in forest cover in Acholi region (15).

Spatial Distribution of NDVI Trends in Northern Uganda in the Conflict and Post-conflict Periods and suggested explicative drivers

We look into biological activity (photosynthetic activity) that results from both natural and planted vegetation (agriculture). Therefore, increase/decrease vegetation activity does not mean there is an increase/decrease in natural vegetation or biodiversity. Nevertheless, photosynthetic activity is a valid proxy for studying the status and change of vegetation as we will show later.

We studied vegetation trends using remote sense analysis and the Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) which have been used to study vegetation dynamics and phenology and trends in vegetation greenness in diverse geographical contexts. For a detail methodological explanation of our study see Nardi & Runnström (2024).

It becomes visually apparent when comparing the NDVI trend maps (Figure 1) that areas with positive trends (in green) are more abundant in the post-conflict period (B) in comparison to the conflict period when larger areas show negative trends (in red) (A).

At this scale of analysis, it is then possible to conclude that Northern Uganda has been turning greener after the cessation of hostilities (B). In the drought stricken Karamoja a ‘greening’ process seems to be taking place since the conflict ended and during the period of analysis (2008-2018), contrary to the conflict period when large extents of areas showed negative trends in vegetation activity (2002-2008).

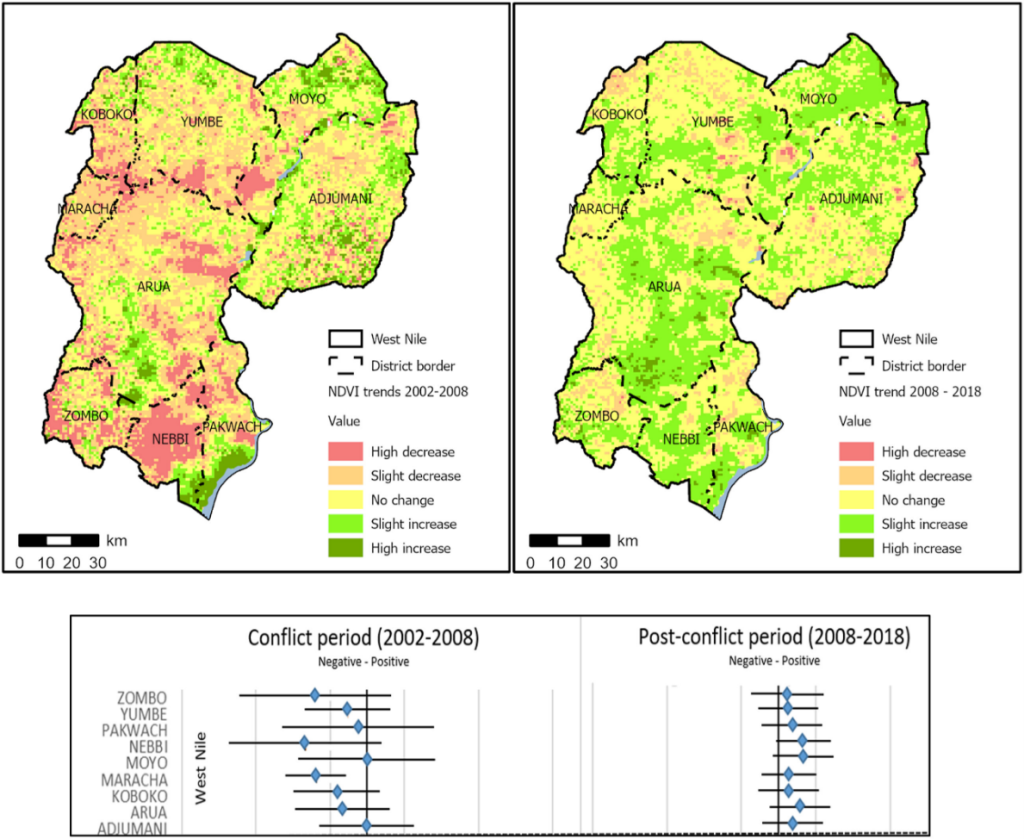

In general terms, we observe that half of the sub-regions under study (four out of eight): north of Bunyoro, Karamoja, Lango, and West Nile have increased vegetation activity between the conflict and post-conflict periods. West Nile stands out due to the larger difference in mean NDVI trend indicating a positive change in vegetation activity.

On the contrary, the remaining four sub-regions show a reverse trend from positive during the conflict period to negative in the post-conflict period or decreasing positive trends, namely, Acholi, Bukedi, Elgon, and Teso. Two sub-regions stand out in this regard – Bukedi and Elgon – due to the greater difference in the mean NDVI trend in comparison with the rest of the sub-regions.

At district level, it is noticeable that most of the area from all the districts in West Nile and Karamoja sub-region have turned negative or stable NDVI trends in the conflict period into positive ones in the post-conflict period of analysis. Karamoja shows the highest positive trends in all its districts during the post-conflict period where no negative cases are found. On the contrary, all districts in Bukedi and most in Elgon show opposite trends between the periods studied. Elgon sub-region stands out due to the severity of the negative trends in the post-conflict period in comparison to all the districts studied.

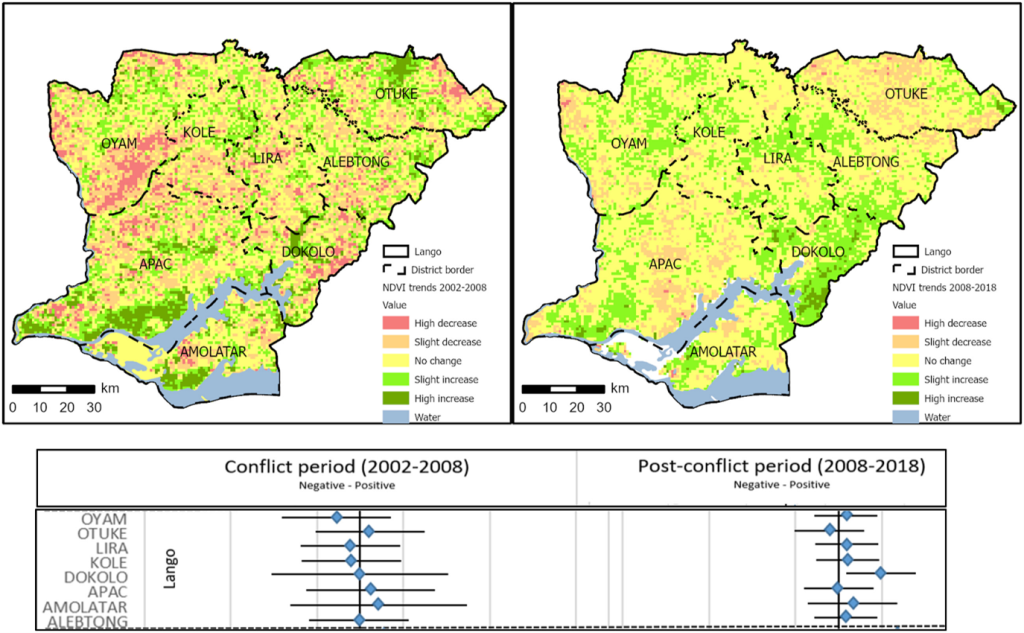

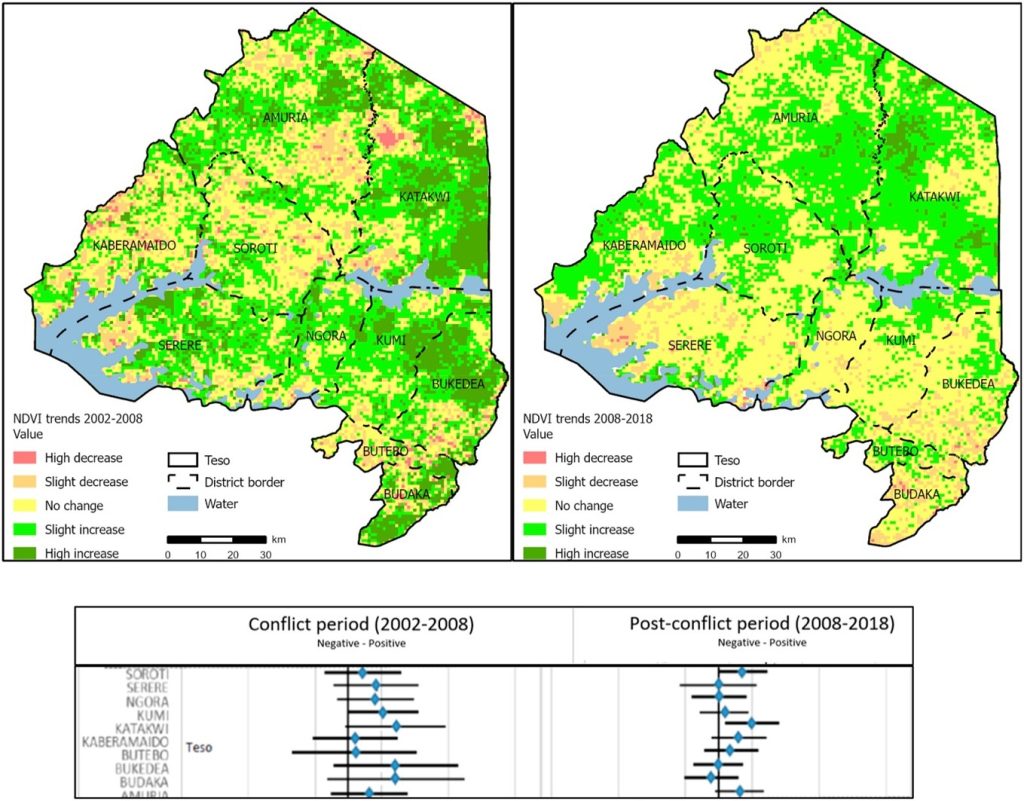

During the conflict and post-conflict period of analysis, districts in Lango show dissimilar NDVI trends on average as in the case of districts in Acholi, with some districts presenting negative and others, positive trends. The districts in Teso show that high positive trends during the conflict period have changed to moderate but still positive trends in the post-conflict period.

Finally, a common pattern in all districts studied is that there is less variation of extreme (positive-negative) NDVI trends in the post-conflict period of analysis in comparison to the conflict period of analysis. This is evidenced by the statistical analysis which shows that the standard deviation is smaller in the post-conflict period compared to the conflict period.

In conclusion, there are two issues that stand out from this descriptive analysis: (a) many areas in the Northern region have become ‘greener’ and (b) the standard deviation of NDVI trends within each sub-region has shortened.

First, in relation to the ‘greening’ of the environment in Northern Uganda, we consider that two drivers might be explaining this. Studies conducted around our second period of analysis (2018) show that agricultural land has been expanding in the region, sometimes in detriment of woodlands and forest (7, 15, 22). Agricultural land has increased, particularly in West Nile and Karamoja (15). Various policies and interventions put in place by the government of Uganda to promote and support farming in the Northern region aiming at ‘boosting agriculture through provision of inputs like improved seeds and seedlings, hoes, tractors and ox ploughs, among others’ (22, page 353).

Second, the shortening of the variation of NDVI trends means that extreme cases of positive-negative trends became more evenly distributed across space in the Northern region. We suggest this could be explained by a more equal distribution of vegetation growth/deterioration, compared to previous unequal geographies of environmental change during the armed conflict.

Based on the literature reviewed, our proposition to explain this is that the relocation of people from IDPC back to their lands and the expansion of economic activities in the Northern region during post-conflict meant a de-concentration of resource exploitation, the degradation of previously preserved areas, the restoration of vegetation in conservation sites, and the expansion of agriculture or other types of vegetation growth (e.g. grasslands, planted forests, etc.).

In addition, the expansion of infrastructure and urban centres (including refugee camps) might be explaining hotspots of vegetation deterioration.

Vegetation and Environmental Change at Sub-regional Level

Our spatial focus of analysis now turns to the four selected sub-regions and their districts: West Nile, Acholi, Lango, and Teso. For further discussions about vegetation change at district level, see Nardi & Runnström (2024).

West Nile Sub-region

West Nile sub-region stands out because mean NDVI trends in the conflict period (2002–2008) were negative in all its districts (except for Adjumani and Moyo that show no changes) and this was reversed in the post-conflict period when all the districts show positive mean NDVI trends (Figure 2). We propose that the ‘greening’ trend in West Nile might be attributed to the conversion of degraded forestlands to crop lands and the shift from subsistence to commercial/plantation farming.

Negative NDVI trends (shown in red) during the conflict period might be attributed to forest degradation. The boom in smoked fish trade between 1990 and 2000 resulted in overexploitation of forests for fuel wood, leading to a loss of over 70% of forest cover along the Nile during that period (15). But other drivers might explain the ‘redness’ of West Nile before 2002, such as population growth, including the influx of refugees into camps, which greatly contributed to resource extraction and vegetation deterioration (23), particularly in woodlands of Adjumani and Moyo districts (16). However, both districts showed an increase in vegetation activity in the post-conflict period of analysis. The discovery and exploration of oil and gas in the Albertine rift has also negatively impacted natural vegetation albeit more localised in West Nile.

We propose that deterioration of woodlands and forests due to resource extraction for fuel and housing might be explaining the ‘redness’ of West Nile in the conflict period 2002-2008.

Conversely, the greening of the sub-region until 2018 might be attributed to increased agricultural area.

Acholi Sub-region

This sub-region shows dissimilar trends at district level. We propose that the negative NDVI trend in some areas after the conflict might be explained by the conversion of natural vegetation – restored during the armed conflict – to agricultural land or urban land use, which also increased between 1996 and 2013 in Acholi.

As the general trend, Acholi sub-region shows a decrease in extreme cases of vegetation deterioration/growth at district level.

Research has observed notable changes in land use and cover between 2006 and 2016 in some parts of Acholi (Aswa iii sub-catchment) where woodlands decreased, small-scale farming increased, while grasslands remained the dominant vegetation during the period until 2018 when agriculture and grassland were evenly distributed in all the area under study (22). Commercial large-scale agriculture has also increased in this sub-region during the post-conflict in Nwoya and Amuru districts between 2009 and 2019 (8).

Acholi sub-region – together with West Nile – is the main charcoal producer in Northern Uganda (10). The sub-region has a comparative advantage over other areas of Uganda for charcoal production because vegetation has been preserved during the armed conflict (24).

Acholi stands out for the increase in urban land between 1996 and 2013 (15). Urbanisation might explain hotspots of vegetation degradation in Acholi during the post-conflict period.

In conclusion, we propose that agriculture might be one of the central drivers explaining the greening of the natural environment in Acholi sub-region, over areas previously degraded, and logging and grassland degradation seem to explain vegetation degradation in areas previously restored and/or preserved during the conflict.

Lango Sub-region

South of Acholi sub-region, Lango accommodated IDP by hosting sixty-one camps all closed by 2009 (UNHCR, 2009). We propose that the mean NDVI increment observed in different districts in Lango might be explained by the increase of land for agriculture and/or grassland as already observed others for the first decade of the conflict (4).

The statistical analysis shows that mean NDVI trend in the post-conflict period becomes much shorter in terms of variation in the increase/decrease of photosynthetic activity, which means that vegetation deterioration/growth becomes more evenly distributed in the sub-region (Figure 4).

During the post-conflict period, most of the districts show positive mean NDVI trends (except for Otuke). Dokolo stands out during the post-conflict because the majority of the surface of the district shows positive NDVI trends. In this district can also be found the highest positive mean NDVI trend of the sub-region. Based on secondary data, we consider that these tendencies might be explained by (a) expansion of agricultural land and forest regeneration or afforestation (e.g. 2099 ha of Kachung Forest Project) in the case of Dokolo (25) and (b) negative change in woody cover (e.g. Otuke) (26).

Teso Sub-region

Ten years ago, ACCS (2013) observed that Teso not only has experienced numerous armed conflicts but also cattle raids, which greatly impacted vegetation (natural and agriculture). Together with Karamoja, this sub-region is currently suffering from drought and floods that have destroyed crops, increased food insecurity and emigration (7).

During the conflict period (2002–2008) mean NDVI trends were positive for all districts in the sub-region, with some districts in particularly standing out due to the high mean positive NDVI trends. In the post-conflict period positive trends remained for all the districts (but Budaka, which showed a negative trend (Figure 5).

We propose that the positive NDVI trends in Teso might be explained by forest regeneration or afforestation. The ‘greening’ of Teso sub-region during the post-conflict period might differ from previous sub-regions studied as it seems to be forestland and not agricultural land that might be explaining this trend. Nevertheless, there are differences within the sub-region and statistical analysis shows that there is a tendency between both periods towards vegetation deterioration. In addition, similar to the other sub-regions, in the post-conflict period, the gap between vegetation deterioration-growth has shortened within each district compared to the conflict period 2002-2008. This means that there are not extreme cases of vegetation deterioration/growth.

Prospects for Sustainable Peace and Development

Our study has shown that some of the sub-regions and districts in Northern Uganda have been turning greener since the armed conflict. We have also proposed that this might be explained by the expansion of agriculture. However, other drivers might be at play. Indeed, forest restoration and/or expansion of woody cover and grassland, as in the case of Teso might be pointing to this.

The conservation of natural vegetation (grassland, forest) or previously degraded areas to agriculture crops might be indicating that the region has not been turning more biodiverse rich during the post-conflict. If the greening of Northern Uganda is explained by agriculture expansion, then we propose that there has been environmental deterioration to a certain degree, as agriculture implies the loss of wildlife habitats and biodiversity erosion. While agriculture might be conducive for food security and economic growth, the way it is organised and articulated with the natural vegetation is central for its sustainability, as well as for an equal development. If agriculture is motorised by large-scale monoculture of industrial crops in detriment of small-scale family-oriented crops and/or expands over forest and woodlands, biodiversity might be compromised along with ecosystem services central for local populations, for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Further research is needed to properly understand positive trends in vegetation activity (e.g. ‘greening’) as well as the impact of agriculture on biodiversity (e.g. use of agrochemicals and water and soil pollution).

The study has also shown that the geographical scale of vegetation change (degradation and restoration) during peace times has changed compared to conflict times and in different scales. Our NDVI study during the armed conflict and during the post-conflict shows that the geographical distribution of vegetation deterioration and growth has become more equally distributed in all sub-regions studied at the district scale of analysis. In this sense, Northern Uganda’s unequal geographies of environmental change have transformed. While it is possible to argue that vegetation is not further depleted during peacetime, it is also the case that vegetation is no longer being restored in the same intensity as during conflict time at regional scale. This should be further corroborated on the ground to properly understand the drivers. However, it is important to consider how scale matters here. Hotspots of deterioration (e.g. refugee camps or forest encroachment) can be observed if we use another geographical scale of analysis than the one used in this study (focused on sub-regional and district level). Future studies could look into other scales of vegetation and environmental change (sub-counties or parishes level).

What might these regional and sub-regional trends and possible explanations be indicating in terms of sustainable peace and development in North Uganda? If we understand agriculture expansion, along with infrastructure expansion, as signs of ‘progress’ and ‘economic growth’ we might conclude that Northern Uganda is undertaking processes of ‘development’ during the post-conflict period of analysis. However, it is important to question whether this development is sustainable and inclusive as well as the implications for peacebuilding. The management of natural resources during post-conflict peacebuilding should be carefully monitored in order to promote conflict-sensitive development and avoid resuming (armed) conflicts.

Our explicative analysis based on secondary data shows that environmental concerns and conflicts in the region in the post-conflict period of analysis might be related to the extensive use of land for agriculture, encroachment over wetlands and local forests, which might be indicating the unsustainability of this development model. While the local population continues to meet their fuel demands on biomass (charcoal and firewood), and their food needs on subsistence cultivation, environmental degradation will continue to play a key role in the sustainable development of the region as local communities are highly dependent on their natural environment for their livelihoods. At the same time, the expansion of large-scale industrial agriculture (e.g. sugar cane), oil exploration and exploitation or hydropower or carbon offsetting projects driven by corporations might further fuel land and environmental conflicts with local communities, as recently shown by environmental defenders in Northern Uganda. This – we propose – might weaken peace consolidation in the region, irrespectively of the ‘greening’ tendencies we observe during the post-conflict period of analysis (2008–2018) in some parts of the region.

Policy Implications

We suggest that future development policy should continue to have a particularised approach to Northern Uganda as peace is not yet consolidated. We propose that future research on vegetation and environmental change in Northern Uganda pays careful attention to dynamics of LULC on the ground and the implication of these uses and changes in natural resource exploitation and management. Our NDVI study could serve as a starting point to identify at local level processes of vegetation restoration and deterioration worth observing.

References

(1) Bruch C., Batra G., Anand A. with Chowdhury, S. & Killian, S. (Eds.), (2023). Conflict-sensitive conservation. Routledge.

(2) Brusset E. (2016). Evaluation of the environmental cooperation for peacebuilding programme. Post-conflict and disaster management Branch (PCDMB), United Nations Environment Programme.

(3) ACCS. (2013). Northern Uganda Conflict Analysis. Advisory Consortium on Conflict Sensitivity: Refugee law project, Safeworld & international alert.

(4) Nampindo S., Picton-Phillipps G., Plumptre A. (2005). The impact of conflict in Northern Uganda on the environment and natural resource management. USAID and Wildlife Conservation Society.

(5) GoU. (2015). The peace, recovery and development plan 3 for Northern Uganda (PRDP3). July 2015-June 2021. Republic of Uganda.

(6) Branch A. & Martiniello G. (2018). Charcoal power: The political violence of non-fossil fuel in Uganda. Geoforum, 97, 242–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.012

(7) NEMA. (2019). National state of the environment report 2018-19. National Environment Management Authority, Government of Uganda.

(8) Luwa J. K., Bamutaze Y., Mwanjalolo J. G. M., Waiswa D., Pilesjö P., Mukengere E. G. (2020). Impacts of land use and land cover change in response to different driving forces in Uganda: Evidence from a review. African Geographical Review, 40(4), 378–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2020.1832547

(9) Serwajja E., Kisira Y., Bamutaze Y. (2024). ‘Better to die of landslides than hunger’: Socio-economic and cultural intricacies of resettlement due to climate-induced hazards in Uganda. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 101, Article 104242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104242

(10) Haysom S., McLaggan M., Kaka J., Modi L., Opala K. (2021). Black gold. The charcoal grey market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan. Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

(11) World Bank. (2018). Rapid assessment of natural resources degradation in areas impacted by the south Sudan refugee influx in Northern Uganda. Technical Report, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank and FAO.

(12) Olanya D. R. (2014). Asian capitalism, primitive accumulation, and the new enclosures in Uganda. African Identities, 12(1), 76–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2013.868672

(13) Serwajja E. (2014). An investigation of land grabbing amidst resettlement in post-conflict Amuru district, Northern Uganda. [PhD thesis, University of the Western Cape].

(14) UBOS. (2021). 2021 statistical abstract. Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

(15) Li J., Oyana T. J., Mukwaya P. I. (2016). An examination of historical and future land use changes in Uganda using change detection methods and agent-based modelling. African Geographical Review, 35(3), 247–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2016.1189836

(16) GoU. (2015). State of Uganda’s forestry 2015. Report. Ministry of Water and Environment.

(17) UBOS. (2021). Uganda national household survey 2019/2020. Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

(18) Ochola D. (2021). Black gold: Illegal logging for charcoal wipe out rare trees in Northern Uganda. Online news. Zenger News. https://www.zenger.news/2021/06/07/black-gold-illegal-logging-for-charcoal-wipe-out-rare-trees-in-northern-uganda/ (Accessed 02 12 2022).

(19) TNH. (2015). Charcoal boom a bust for forests. Online news. The New Humanitarian. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/report/94810/uganda-charcoal-boom-bust-forests (Accessed 02 12 2022).

(20) Mugizi F. M. P., Matsumoto T. (2021). From conflict to conflicts: War-induced displacement, land conflicts, and agricultural productivity in post-war Northern Uganda. Land Use Policy, 101, Article 105149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105149

(21) MWE. (2016). State of Uganda’s forestry. Ministry of Water and Environment, Government of Uganda.

(22) Oguzu B., Egeru A., Nyeko M., Obia A., Barasa B. (2018). Land use/cover change in Aswa III sub-catchment, Northern Uganda. RUFORUM Working Document Series, 17(1), 349-356.

(23) Hughes R., Owen M., Verheijen L., Kasedde C., Oule H., Begumana J., D’Aietti L., Gianvenuti A., Jonckheere I., Kintu E., Lindquist E., Tavani R., Xia Z. (2020). Rapid assessment of natural resource degradation in refugee impacted areas in Northern Uganda. Technical Report June 2019. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and World Bank.

(24) Kaguta V. (2022). Failed implementation of the reforestation policies depleting forest cover in Northern Uganda. Online news. New Vision. https://www.newvision.co.ug/category/news/failed-implementation-of-the-reforestation-po-132700 (Accessed 02 12 2022).

(25) Edstedt K., Carton W. (2018). The benefits that (only) capital can see? Resource access and degradation in industrial carbon forestry, lessons from the CDM in Uganda. Geoforum, 97, 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.030

(26) Ojok O. (2020). Why we must act to protect our Shea trees. Opinion. Nile Post. https://nilepost.co.ug/2020/11/12/why-we-must-act-to-protect-our-shea-trees/ (Accessed 01 07 2023).