‘The Nature of Peace’: exploring links between the natural environment and peace-building in post-conflict societies

About The Nature of Peace research group

This conference is organized by the interdisciplinary research group ‘The Nature of Peace’ at the Pufendorf Institute of Advance Studies at Lund University, Sweden. The research group scrutinizes the role of the natural environment in post-conflict societies, posing questions such as: What role does nature have in peace building? How is the natural environment considered in fragile states that need to develop quickly, during reconstruction period? Does peace always bring sustainable development? How can peace-building activities contribute to sustainable development?

The research group brings together researchers from five different faculties (Social Sciences, Law, Humanities and Theology, Natural Sciences, and University Specialised Centres) to discuss and work on these issues.

Why the Nature of Peace?

Empirical evidence from around the world has shown that post-conflict reconstruction efforts often focus on the short-term and urgent needs of societies transitioning to peace. These processes, however, often fail to consider the root causes of the conflict (such as control over key natural resources) or to integrate post-conflict dynamics such as those linked to the distribution of environmental “goods” (water, land, forest, etc.) and “bads” (pollution, contamination, enclosures, etc.), the participation and restriction in environmental politics by diverse ethnic/social/gender/age groups, or the recognition and denial of diverse value systems with different understandings of nature and human.

In order to present its research results, the research group is organizing a two-days final conference to take place in Lund on the 26th and 27th of April 2018. We intend that the conference serves as well as a platform to engage with different people working with related issues. Therefore, we would like to invite other scholars and practitioners to participate or present their work.

Final conference

The conference is structured in a series of seminars and a panel. We expect to have few papers in each seminar to allow for in-depth discussion and engagement. We intent that the seminars would give presenters the space to share ideas or hypotheses, elaborate on them and debate about the role of nature in post-conflict societies from diverse perspectives. Presenters will be able to choose the best way to communicate their ideas and engage the audience in discussions using different methods (e.g. from a classical power point presentation to a more interactive one such as using on-line tools). In the panel, participants will have the opportunity to share their views from the ground.

The conference is structured in six seminars and a panel:

- Natural resources exploitation

- Environmental legislation / nature governance

- Biodiversity conservation

- Monitoring environmental transformation (tools and mechanisms)

- Nature, culture and rights

- Intersectionality, post-conflict and natural environment

- Panel: Local perspectives

In Seminar 1 “Natural resource exploitation” we welcome papers that address the relevance of focusing in natural resource exploitation in different scales. Natural resources (land included) are target of international investors and corporations and national states take advantage of them to promote economic development and foster state reconstruction. However, natural resources are key for local livelihoods and income generation. Disputes over the access and use of natural resources (such as diamonds or forests) can create new conflicts or bring back old ones, attempting against stability and peace in the long run.

In Seminar 2 “Environmental legislation / nature governance” we invite papers that address, for instance, the following questions: Which major governance processes relating to the natural environment (agenda-setting, rule- and decision-making, implementation, enforcement, evaluation) have taken place in post-conflict situations, which ones are missing? What are the major outputs (laws, strategies, guidelines, incentive mechanisms, etc.) and how effective are they? Which actors have been involved in these processes or benefited from them (international or domestic actors; governmental, civil society, private sector, military, scientists, vulnerable groups, other stakeholders), which ones have been absent or marginalized? At which levels have these processes predominantly taken place (national, regional, local)? What is the degree of legitimacy and accountability of post-conflict environmental governance and legislation? And how can we explain or understand the observed types of governance, inclusiveness, effectiveness or legitimacy in a theory-guided manner, e.g. through constellations of power and interests, knowledge claims and gaps, or the contestation of norms and discourses?

In Seminar 3 “Biodiversity conservation” we invite papers that inquire to what extent peacebuilding can potentially bridge developmental objectives with biodiversity conservation. A transition towards post-conflict opens an opportunity to retake control over protected areas, forest ecosystems and biodiversity. Yet, biodiversity conservation is not very high on the peacebuilding agenda and with political stability and security comes development of infrastructure and certain economic sectors that further drive the loss of biodiversity. New roads provide easier access to remote areas and lead to an increase in hunting, degradation of ecosystems and the loss of habitat, affecting biodiversity negatively. Counteracting this negative trend with serious long-term implications for the health of people and ecosystems is fundamental and post-conflict transitions provide a window of opportunity towards a more sustainable use and conservation of biodiversity.

In Seminar 4 “Monitoring environmental transformation” we seek to discuss the possibilities to use Earth observations from satellite to monitor natural environments and resources in post-conflict situations. Time series of satellite images analyzed in a geographic information system (GIS) are objective means to access status and changes in environmental parameters e.g. spatial distribution and area of different land use, land use changes, biological production, and natural forest area issues. Earth observation methods, together with contextual information and data collected with other methods, might be able to tell us something about how socio-economic and political changes lead to inequalities among different groups and across socially constructed boundaries, particularly in peacebuilding. This seminar also intends to include debates regarding what we can and cannot say about nature in post-conflict situations using satellite images.

In Seminar 5 “Nature, culture and rights”, we invite presentations focusing on how cultural beliefs and practices, especially the relationship between human beings and the non-human world, can be of relevance for post-conflict peace-building. Culture can be defined as a body of beliefs and practices in terms of which a group of people understand themselves and the world and organize their individual and collective lives. These beliefs, practices and value systems might be shaped by religion, but also by Enlightenment ideas about rationality, secularism and progress, and be a reflection of power dynamics within or between societies. Both theoretical discussions from fields such as philosophy, religious studies and human rights studies, as well as case studies from local contexts, are invited.

In Seminar 6 “Intersectionality, post-conflict and natural environment” we particularly welcome papers interested in addressing gender aspects that relate to nature in post-conflict and peacebuilding. However, we have a broad understanding of intersectionality, referring to overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination, oppression, and disadvantage according to social categorizations not only gender but also ethnicity, social class, age, sexuality, etc.

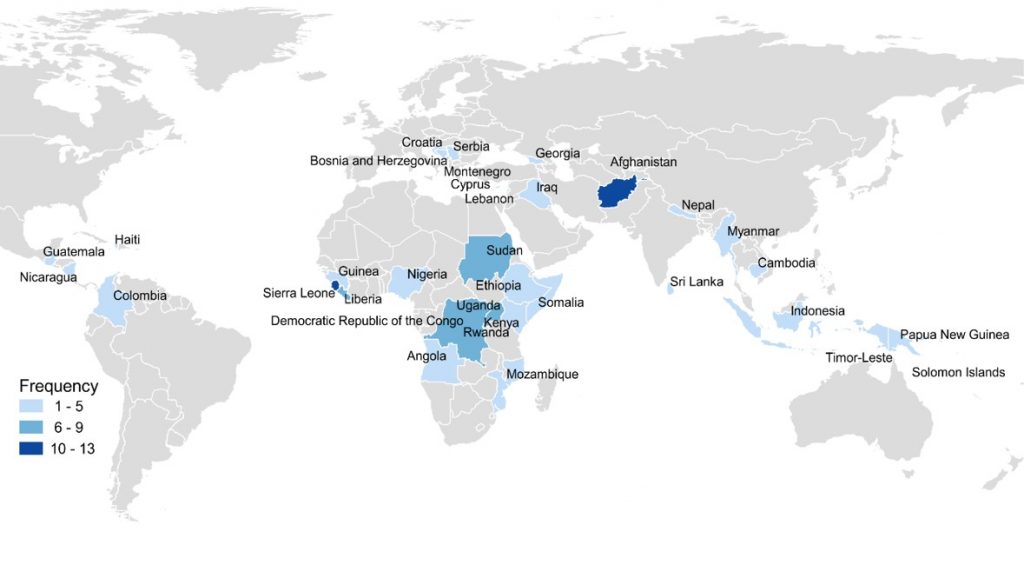

The panel “Local perspectives” invites practitioners (including activists, politicians, lawyers, NGO staff working on the ground) working with local communities from different continents in post-conflict situation and/or peace-building to present their views from the ground. With this panel we want to show regional differences in relation to how the natural environment and peacebuilding are interconnected (or not).

Participation and contact

Papers interested in discussing the role of nature in post-conflict societies and/or during peacebuilding are welcome!

If you would like to participate, please send an email to Andrea Nardi (andrea.nardi@keg.lu.se) or Lina Eklund (lina.eklund@cme.lu.se). If you are interested in presenting a paper, please submit an abstract and the name of the seminar you would like to do so.

Submissions should consist of a text with no more than 500 words and a brief CV containing the author’s name, institutional affiliation and contact information. We should receive the abstract no later than 15 February 2018. All participants will be notified of the final selection by 28 February 2018.

Comments