By Fariborz Zelli

Three weeks ago, the 16th conference of the parties (COP) to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) ended in the Colombian city of Cali. In the 32-year history of these biannual meetings, the negotiations during the Cali COP were remarkable in various regards, for both achievements and disappointments – and for similarities to the UN climate COP that took place in Baku only two weeks later.

1. The Official Negotiations: Making somewhat peace with Nature

What worked well…

Arguably the biggest success – and where the COP delivered mostly on its motto “Making Peace with Nature” – was the progress made on Article 8 (j) of the biodiversity convention. The article highlights the importance of traditional knowledge and practices, and hence directly relates to the role that indigenous and other local communities play for safeguarding biodiversity around the planet. With the headway made on these questions, the Cali COP has also vital implications for our Lund-based team’s research on the role of environmental human rights defenders (EHRD).

The discussions around Article 8 (j) had been key for the Colombian hosts around conference President and Colombian environmental minister Susana Muhamad as well as for the Colombian government under President Gustavo Petro. Thanks to the diplomacy of the COP leadership, delegates agreed in the final hours to establish a new subsidiary body to protect indigenous communities and local populations as defenders of nature. They further decided to acknowledge the role of people of African descent in the implementation of the biodiversity convention, going back to another initiative tabled by the conference hosts.

With their decision the delegates created the precedent of placing a political organ dedicated to indigenous communities and human rights under the auspices of a global environmental institution – and they thereby recognize the strong overlaps between biodiversity and human rights. While the new subsidiary body now must be filled with life, its sheer establishment guarantees that concerns of indigenous and local communities will be more strongly integrated in discussions and decisions at future biodiversity COPs. Beyond the immediate context of the CBD, the body provides a new frame of reference with an institutional underpinning for EHRDs across the globe. Ideally, it can help facilitate a much-needed denser network of international and domestic law to protect indigenous and local communities in biodiversity hotspots.

This conference outcome is even more notable as Colombia is the country with the highest number of assassinations of EHRDs worldwide. This sad figure is, absurdly, connected to the country’s peace process, which had started in 2016 when an accord between the Colombian government and the FARC rebels ended an over fifty years long civil war. With the FARC giving up control over a large part of Colombian territory, the lands of indigenous, peasant, Afro-descendant and other local communities also became accessible to new threats, from legal and illegal mining to the expanded areas of operation of Colombian, Mexican and other international drug cartels. The new CBD subsidiary body will not be able to solve these problems fundamentally, but it may alleviate some of them – by more widely acknowledging the efforts that EHRDs in Colombia and elsewhere are making to protect nature in conjunction with their own cultures and livelihoods.

The Cali COP also saw progress on further important topics. This includes another agenda item of high relevance for indigenous and local communities, and for North-South relations in general. Delegates agreed on a new multilateral mechanism to fairly share the benefits from the use of genetic resources, and to do so based on genetic sequences of biodiversity stored in databases. Companies who use such digital sequence information (DSI) are now expected to pay a portion of their profits and revenues to the new ‘Cali Fund’. This would apply, for instance, when plant genetic resources with an origin in Sub-Saharan Africa or the Amazon are used by pharmaceutical companies in the Global North. Notably, 50% of the fund shall be allocated to indigenious peoples and local communities. Since the new mechanism is voluntary, however, companies are under no legal obligaton to compensate countries of origin or respective actors therein.

What didn’t work well…

Notwithstanding these and other positive results – e.g. on mainstreaming biodiversity into infrastructure, and, after eight years of negotiations, on a new process to identify ecologically significant marine areas – the Cali COP leaves behind a lot of unfinished business. No significant progress was made on two of biodiversity negotiations’ major bones of contention: 1) on implementing the new core of the CBD treaty family, the 27 goals of the 2022 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which had been adopted at the last COP in Montreal; and 2) on the financial mechanism and resources to support respective implementation efforts. Negotiators could not reach substantial agreement on neither of these two essential matters. In fact, with an increasing number of delegates leaving for their flights home, the COP plenary was no longer permitted to take any decisions in the final conference hours. Instead, the conference was suspended unceremoniously, with a resumed meeting expected to take place in the coming months.

When it comes to the first controversial aspect of implementation mechanisms, delegates at Cali could not fill important gaps in the so-called “stocktake” – a global review process, which, by 2026, shall hold countries accountable for implementing the GBF. To be fair, this implementation and review gap of biodiversity negotiations is the consequence of a more fundamental problem that marks global environmental diplomacy today: a hollowing-out of what is actually multilateral in the respective treaties and agreements, with things not adding up.

Environmental diplomacy has never been easy, seeking to address systemic and complex problems while often being down-prioritised in comparison to international security or trade. Over the past ten years or more, however, we have been witnessing a particular trend in global environmental politics: Major negotiations provide ambitious but voluntary goals while not specifying what the specific contributions of each country, or at least some countries, to these goals should be (as was still the case e.g. in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on climate change). Instead, each country may come up with their own individual implementation plans and objectives, which only undergo voluntary review processes and which, when added together, are far from reaching the overarching goals.

The GBF with its ambitious, yet non-binding set of 27 targets is just the last prominent example for this logic of window-dressing of multilateral environmental deals. Others include the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the Paris Agreement on climate change with its 1.5°C goal, both adopted in 2015 and, like the GBF, built around ambitious and internationally renowned goals while leaving essential questions of individual country contributions and implementation out of the multilateral package. The voluntary country reports may bear different names and acronyms in these three contexts – VNRs (Voluntary National Reviews) for the SDGs, NDCs (nationally Determined Contributions) for the Paris Agreement, and NBSAPs (National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans) for the GBF. But with the first rounds of these reports coming in, they share similar degrees of disappointment: Based on the VNRs the 2024 SDG Report revealed that only 17% of the SDG targets were on track for 2030; summing up all NDCs we can no longer exclude the possibility of surpassing 2.9°C of global warming by 2100; and before CBD-COP16 more than 80% of the 196 parties to the GBF had missed the deadline to submit their revised NBSAPs.

With this fixation on voluntary goals as the in-built problem of international environmental diplomacy today, it should not come as a surprise that the implementation gap is haunting COPs like the one in Cali. Negotiators and observers show a lot of good will and insight and discuss all sorts of mechanisms for implementation and review until the last minute, but these hardly find their way into decisions.

The same window-dressing deja vu applies to financing, the second major contentious issue in Cali. Once again not unsimilar to climate negotiations (with e.g. the Green Climate Fund or the new Loss and Damage Fund), it is comparably easy for countries to agree on joint financial targets rather than on specific activities to keep these promises, e.g. on a mechanism like the Cali Fund on benefit sharing. Similar to major sets of targets like the GBF in 2022, a new fund makes for a presentable final conference result to the media. Yet, agreeing on a fund as such keeps more important and more sensitive modalities unaddressed, e.g. how much certain countries actually should and will contribute, or how voting rights on the use of the funds are distributed. An illustration of the divergent views on these specific questions is a 98-page-long non-paper published by delegation co-chairs at Cali, packed with wishlists on resource mobilization through 2030 that negotiators could not agree on.

Taking this into account, the failure to establish a proper global biodiversity financing mechanism at Cali, no matter how superficial, is outright underwhelming. The CBD now must continue working with an interim trust fund, the 2023 Global Biodiversity Framework Fund, for which pledges have been comparatively low in Cali. With currently a bit over US$ 400, the fund falls significantly short of developed countries’ commitments to provide US$ 20 bn annually in international biodiversity financing by 2025.

The story behind this failure is not only one of lack of willingness of developed countries to accept larger responsibility for global biodiversity loss. It is also a story of power and political control. In the absence of a proper CBD fund, the interim financing mechanism is operated by the Global Environment Facility (GEF), a multilateral financial institution whose funds are administered by the World Bank and that has provided grants for environmental protection activities in developing countries since 1991.

Funding decisions are taken by the GEF Council which consists of 14 members from developed countries, 16 from developing countries, and two from economies in transition – a constellation that allows donors to keep considerable control over where their money is going. By contrast, a global financing instrument for biodiversity under the authority of the COP, as conference President Susana Muhamad suggested on the last day in Cali, would have given developing countries a voting majority over these financial flows. By rejecting such an instrument, developed countries prioritised their control as donors over substantial progress on global biodiversity protection.

This outcome is even more underwhelming when taking into consideration that Cali negotiations were not severely affected by US elections. Unlike for the current climate COP in Baku where the US delegation is a lame duck, the Cali COP ended three days before Trump’s victory. Due to the missed opportunities at Cali, however, US elections will effectively have a big effect on this COP after all. Even though the US is not a party to the CBD, the incoming administration will cast a shadow on further negotiations, including at the resumed COP in a few months. For the next four years in general, we can expect a considerable drop in US support for UN environmental conferences and their goals, which will also impact the strategies of other parties.

Connected to these disappointments on implementation and financing, the COP has suffered from typical rituals that have become familiar traits of multilateral environmental negotiations over the years. One of these is the who-blinks-first mentality of major negotiationg blocks. Negotiators often wait with major concessions on key issues until the last moments of a COP. This approach entails, first, all sorts of procrastinations during most of the two weeks of the conference, e.g. overproportionally long discussions about technical details, and second, a crescendo towards a melt-down and last-minute spree of decisions. As Cali has shown, this final act may even come too late when most seats in the theatre are already empty.

Another ritual that can hit the brake on negotiations – and certainly did so in Cali – was the typical high-level segment in the second week of environmental COPs. When heads of states and environmental ministers join negotiations for a few days to address the COP plenary this may well serve to raise the global publicity of negotiations, and of these very heads of states and ministers themselves. However, this intermission of governmental leaders, a type of ‘COP inside the COP’, also tends to interrupt the actual negotiation efforts in the important final phase of the conference.

Related to this, backroom diplomacy at environmental COPs has considerably increased over the last years. To reinvigorate discussions on controversial issues, conference hosts happily act as honest brokers and summon a handpicked selection of country delegates or leaders behind closed doors. However, using such backroom diplomacy as an excessive element can also backfire, as it loses some of its magic and keeps the actual negotiations in waiting. In Cali, those closed doors did not even open in time before too many delegates had left town.

2. Non-Governmental Engagement: Some People’s COP

What worked well…

COP President Susana Muhamad claimed that COP16 in Colombia will be remembered for being “La COP de la gente”, the people’s COP. She has a point with respect to the decisions on indigenous communities and local populations, but also with a view to the wider engagement of civil society and the local public. One of the highlights during the two weeks in Cali was the designated area for civil society activities, the so-called ‘Green Zone’. In recent years, organisers of environmental COPs often carefully choose to spatially separate this area the from official negotiation venue (the ‘Blue Zone’) – for security reasons, but certainly also to avoid disturbances by larger protests. Cali was no different in that regard, with the Blue Zone in a large conference centre on the north end of the city, and the Green Zone being placed in a park right in the heart of Cali.

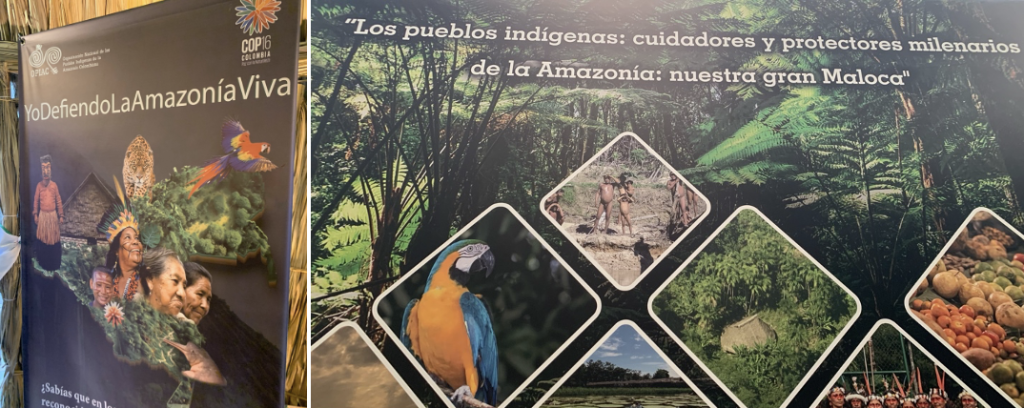

Nonetheless, a benefit of this spatial distance was that the local population took a much stronger interest in Green Zone activities and, especially during the first COP week, turned the zone into a festival of cultural encounters. Many indigenous associations and communities, mostly from Colombia, had come to Cali to present their traditions in numerous exhibits, but also to talk about their needs and the challenges they face in a series of side-events. In these they repeatedly stressed their delicate role as defenders and guards of biodiversity. They reminded listeners that in recent years the loss of primary forest in the Amazon has been significantly lower in indigenous than in non-indigenous territories. In defending their own livelihoods, these communities have become, intendedly or not, frontline implementers of the very Global Biodiversity Framework that negotiators were debating some kilometers further north.

For many Colombians the Green Zone in Cali may have been the first major opportunity for direct exchanges on the indigenous heritage of their country, and about the various threats the respective communities are facing. These encounters and learning processes, one hopes, may contribute to a wider recognition and understanding of the role of environmental human rights defenders – and to preserving traditional ecological knowledge, lifestyles and cosmologies of these communities and their invaluable insights for preserving biodiversity. That alone would make this COP a success story, no matter what happened in the actual conference centre in the outskirts of the city.

What didn’t work well…

With 23,000 registered participants, 46% more than at the previous COP, Cali hosted the biggest biodiversity COP to date. While this number is dwarfed by attendance figures of UN climate conferences (85,000 in Dubai last year; 65,000 at the current COP in Baku), the steep increase from 2022 implied several challenges.

For one, the organization of side-events in the Blue and Green zones was far from optimal, if not outright overburdened. Blue Zone organisers accepted about a quarter of the ca.1,200 proposed events, but only published the selection and actual schedule about a month before the start of the conference. Green Zone organisers took the decision to shorten the original submission period for side-event proposals in the midst of application process. These organizational mishaps posed severe challenges to the activities and travel plans of many civil society actors, especially for those from developing countries.

While figures went up for all types of attendants between the 2022 and 2024 COPs, they did so unproportionally for business and industry delegates. Most of these represented sectors like pharmaceuticals, fossil fuels, agrochemicals and pesticides, food and beverage processing and biotechnology. A total of 1,261 such delegates registered for the Cali COP, more than doubling business representation compared to the previous UN biodiversity summit in Montreal.

To get somewhere near reaching the GBF targets, it no doubt is essential to involve businesses across implementation activities. Without attracting investors and innovators, most of these activities will remain impossible. This notwithstanding, the soaring figures of business delegates raise some concerns. First, if this trend continues it will manifest a systemic imbalance among non-governmental actors in future COP representation, to the disadvantage of e.g. vulnerable communities or scientific institutions.

Second, certain lobbyists may seek to push back progress on key questions, as, for instance, many biotech representatives attempted around negotiations on the new benefit-sharing mechanism at COP16. And third, the large global attention that UN environmental summits are receiving also makes them welcome platforms for greenwashing. To put this carefully: it may have been advisable for organisers in Cali to gauge the possible consequences of business-showcasing in their events more cautiously beforehand.

One example was the advertisement for Smurfit in Cali’s Humboldt House, which organized a total of 180 external events on culture and biodiversity during the COP. Smurfit-Kappa, Europe’s leading corrugated packaging company, has repeatedly been the target of severe accusations by indigenous and campesino communities in Colombia’s Cauca region. The communities are impacted by Smurfit-Kappa’s intensive monocrop pine and eucalyptus plantations and have been trying to reclaim their land from the company. Another multinational met more resistance at Cali. The self-presentation the Canadian company Libero Cobre as a biodiversity champion provoked a protest rally by indigenous communities. The company had acquired four mining titles in southern Colombia in 2018 and since met protests by members of local Nasa and Inga communities for fear of groundwater contamination, forest loss, splitting the community and disregarding rights of prior informed consent. On another note, the Swedish embassy’s decision to host its official reception for Sweden-based COP participants in Cali’s local IKEA store may have raised quite a few eyebrows.

3. The Way Forward – A Tale of two COPs

Many of the challenges mentioned, from implementation and financing gaps to ritualistic aspects, lobbying and greenwashing, have been haunting both UN biodiversity and climate negotiations for years. It thus does not come as a surprise that many of the reform suggestions that are made for UN climate summits are also applicable to biodiversity COPs. At the occasion of the ongoing UN climate COP in Baku, eminent politicians and researchers published an open letter with the Club of Rome in which they urged several reforms – and most of their suggestions sound as if they had been written for the biodiversity COP Cali.

To address the ritualistic and last-minute showdown nature of COPs the authors recommend a “shift away from negotiations to the delivery of concrete action”. To achieve this, COPs could be transformed to smaller, but more frequent and solution-oriented meetings. Such a reform would give delegates more space and time to focus continuously on sensitive but essential modalities of financing and implementation, i.e. to actually fill the envelopes and go beyond superficial establishments on targets and funds. As for implementation, future meetings could ideally be supplemented by enhanced reporting and benchmarking mechanisms to monitor country progress continuously and hold countries accountable for reaching the GBF targets. More targeted COP meetings could direct more negotiating efforts towards criteria for disbursing funds and tracking mechanisms for financial flows, and thereby help overcome the current stalemate over a future biodiversity funding mechanism.

Another side-effect of smaller, more frequent and targeted COPs could be the equitable representation of non-governmental actors. Cutting back to a smaller presence of observers at the official Blue Zone altogether could go hand in hand with balancing figures among business, NGO and scientific representatives – without necessarily having to compromise on the scope of civil society activities in the Green Zone.

Various observers have also called for holding joint climate and biodiversity COPs in the future. Such an approach would have its benefits considering an increasing number of cross-cutting topics, from the impacts of climate change on biodiversity to the use of forests as carbon stocks or the protection of indigenous communities as environmental change agents.

There are some caveats though, and not only given the current sizes of both types of conferences. As the last two world environmental summits – 2002 in Johannesburg and 2012 in Rio – have shown, negotiating too many sensitive aspects in one package may reduce the opportunity of any notable deal at all. Moreover, there is a risk that biodiversity questions are subordinated to certain concerns or logics in climate negotiations. For instance, the latter feature a larger set of market-based approaches like offsetting and tradable certificates. While quantifying carbon limitation efforts is a challenge, doing so for valuing biodiversity may be often impossible, or simply not desirable. One case in point that demonstrates this is the so-called REDD+ mechanism (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) under the UN climate regime. As of 2022 REDD+ activities covered more than 60% of the forest area in developing countries. While the mechanism values and quantifies the carbon storage aspect of forests (by covering opportunity costs of avoided deforestation), it side-lines other important forest functions. The merits of this mechanism notwithstanding, it exemplifies how core aspects of biodiversity are today negotiated from a climate perspective.

Finally, the selection processes of future COP venues need to be overhauled. Delegates in Cali decided that the next CBD COP in 2026 will be held in Armenia. Notably, the main contender was Azerbaijan, the very host of the currently ongoing UN climate conference. To say the least, a UN biodiversity summit should not turn into a sideshow of geopolitical tensions between two neighbouring countries. What is more, as not only the current climate COP shows, the choice of venue can have a severe impact on the course of negotiations, and not always for the better. Praising fossil fuels as a “gift from God”, as Azerbaijani head of state Ilham Aliyev did in his inaugural address to the climate COP in Baku, has set an unfortunate tone for that meeting.

The next biodiversity COP is now spared a similar fate and will not take place in a country where 90% of the export economy relies on oil and gas. Still, we need stricter eligibility criteria for future COP Presidencies. The Cali COP with its achievements on indigenous people and local communities demonstrated what a difference it can make to hold a COP in a mega-biodiverse country with an engaged host government. Let us hope for similarly sensible placements in the future. Addressing the sixth mass extinction is a too serious issue to be left to geopolitics and country greenwashing.